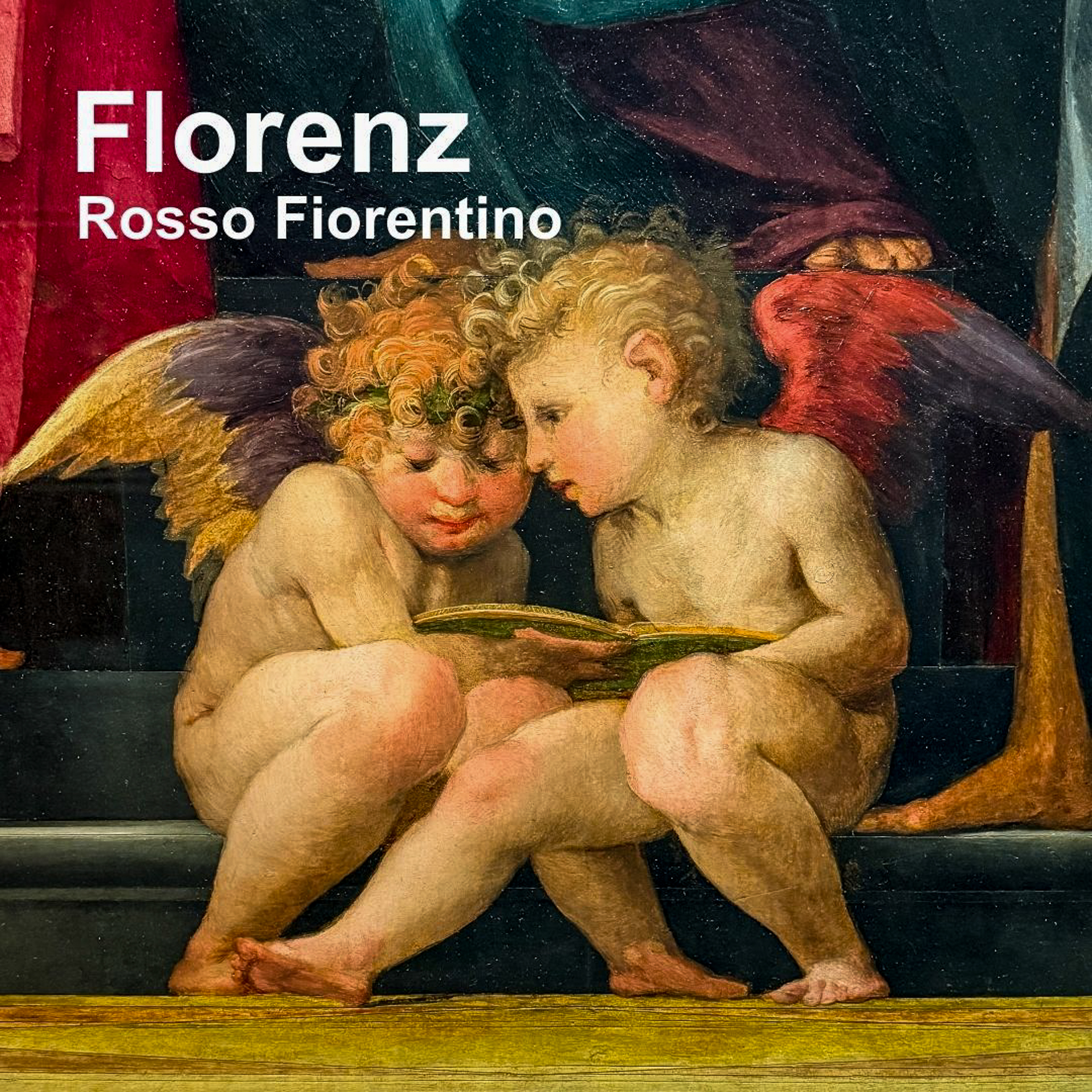

Florenz, Rosso Fiorentino: Detail der Madonna dello Spedalingo. Das hinreißende Engelspärchen beim Nachhilfeunterricht im Lesen oder Singen entstammt einem Skandalbild des jungen Künstlers.

Detail of the Madonna dello Spedalingo. The enchanting pair of angels taking private lessons in reading or singing is taken from a scandalous painting by the young artist.

Ein frühes Skandalbild

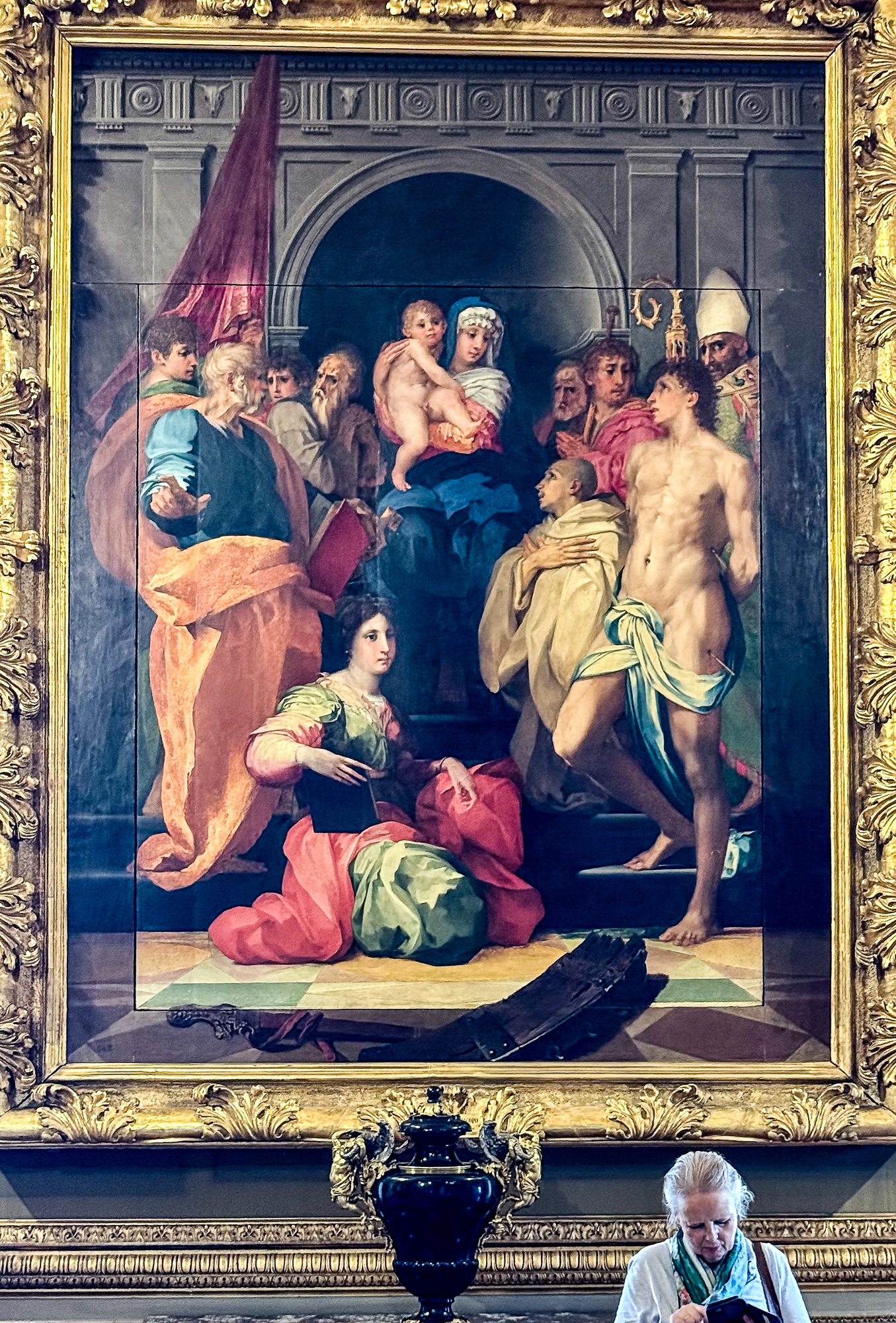

Rosso Fiorentino: Madonna mit vier Heiligen, bekannt als Pala dello Spedalingo, 1518, Tempera auf Holz, 172 x 141 cm, Florenz, Uffizien

Rosso Fiorentino (eigentlich: Giovanni Battista di Jacopo, Florenz 1495-1540 Paris), trägt seinen Namen wegen seiner roten Haare. Vielleicht glichen sie denen von Johannes d. T.

Mit diesem Bild schockiert Rosso den Auftraggeber Leonardo Buonafede (1450-1529), den Spedalingo bzw. Prior des Spitals Santa Maria Nuova. Noch unvollendet, lassen Rossos Gestalten den alten Herrn an Teufel denken. Buonafede zahlt nicht den vereinbarten Preis, die Heiligen im Hintergrund werden ausgetauscht und die Tafel endet in einer Landkirche im Mugello.

In fast beklemmender Enge stehen die Heiligen um die erhöht sitzende Maria mit dem Kind. Es sieht wie dunkel geschminkt aus um die Augen. Das Erschrecken des Priors ist nachvollziehbar. Links der halb wild, halb elegant wirkende Täufer Johannes in ungewohnter Farbigkeit. Gegenüber der total ausgemergelte Greis Hieronymus. Dazwischen eingezwängt Antonius Abbas und der gesteinigte Stephanus. Unberührt von allem das kindliche Engelspaar auf diesem Gründungswerk des florentinischen Manierismus.

An early scandal image

Rosso Fiorentino (actually: Giovanni Battista di Jacopo, Florence 1495-1540 Paris), bears his name because of his red hair. Perhaps they resembled those of St. John the Baptist.

With this painting, Rosso shocked his patron Leonardo Buonafede, the Spedalingo or prior of the S. Maria Nuova hospital. Still unfinished, Rosso’s figures make him think of devils. Buonafede does not pay the agreed price, the saints in the background are replaced and the panel ends up in a country church in Mugello.

The saints stand in almost oppressive confinement around the seated Mary with the child. It looks like dark makeup around the eyes. The prior’s shock is understandable.Es sieht wie dunkel geschminkt aus um die Augen. Das Erschrecken des Priors ist nachvollziehbar.On the left, the half wild, half elegant-looking Baptist John in unusual colors and opposite him the totally emaciated old man Jerome. Sandwiched between them are Antonius Abbas and the stoned Stephen. Untouched by all this is the childlike pair of angels in this founding work of Florentine Mannerism.

Das Meisterwerk in Volterra

Rosso Fiorentino, Kreuzabnahme Christi, 1521, Öl auf Holz, 343 x 201 cm, Volterra, Palazzo dei Priori, Pinacoteca, aufgenommen 2017

Noch unerhörter und farblich überraschender ist das Hauptwerk Rossos in Volterra. Anders als üblich ist hier die Abnahme der bereits verfärbten Leiche eine riskante Angelegenheit: eine harte, gestenreiche und von Geschrei begleitete Arbeit in kreisender Bewegung bei starkem Wind. Unten Trauergestalten: links sackt Maria in Ohnmacht zusammen, gestützt von Begleiterinnen. Kniend umfasst Maria Magdalena ihre Beine, in nie zuvor gesehenem Rot. Rechts großartig gramgebeugt in reicher Gewandung der Lieblingsjünger Johannes. Ansprechend auch ein still beobachtender junger Mann, der eine der drei Leitern hält. Alles in allem ein in Farben und Formen tief beeindruckendes Figurenensemble, das die Ruhe der Hochrenaissance weit hinter sich lässt.

Rosso’s main work in Volterra is even more outrageous and surprising in terms of color. Unlike usual, here the removal of the already discolored corpse is a risky, hard, gestural and screaming work in a circular motion in a strong wind. Below, mourning figures: Mary on the left, slumped over in a swoon, supported by companions. Kneeling, Mary Magdalene clasps her legs in a never-before-seen red. On the right, the favorite disciple John and a quietly observing young man holding one of the three ladders, bent over in rich garments. All in all, a large ensemble of figures, deeply impressive in color and form, which leaves the tranquility of the High Renaissance far behind.

Rosso Fiorentino, Kreuzabnahme, Detail

Florenz, Rosso Fiorentino: ein Altarbild aus Santo Spirito – vergrößert im 18. Jahrhundert

Rosso Fiorentino und Vergrößerung des 18. Jh., Maria mit Kind und Heiligen, Florenz, Palazzo Pitti

Das im 17. Jh. aus Santo Spirito in den Palazzo Pitti überführte Gemälde wurde stark vergrößert, um in einen Barockrahmen zu passen. Damit verliert die Komposition ihre bedrängende Enge, um die es Rosso Fiorentino geht.

Rosso Fiorentino and 18th century enlargement, Mary with Child and Saints

The painting, which was transferred from Santo Spirito to the Palazzo Pitti in the 17th century, was greatly enlarged in order to fit into a Baroque frame. As a result, the composition loses the oppressive narrowness that Rosso Fiorentino was concerned with.zz

Rosso Fiorentino, Pala Dei: Madonna mit Kind und Heiligen (Originaldimension), 1522, Öl auf Holz, 299 x 250 cm, Florenz, Palazzo Pitti

Anstelle von Raffaels unvollendeter Madonna del Baldacchino gibt Ranieri Dei den Auftrag an Rosso Fiorentino. Seine Altartafel für die Familienkapelle in Santo Spirito wird Ende 17. Jh. durch eine Kopie ersetzt. Das Original gelangt in den Palazzo Pitti. Die Rundumvergrößerung des 18. Jh. habe ich hier gelöscht.

Pala Dei: ursprüngliches Aussehen

Maria mit Kind in verwandter Auffassung wie die Figuren der Pala dello Spedalingo. Das Ganze ist jedoch auch ein Echo auf Raffaels nur 14 Jahre ältere Komposition. Statt Raffaels vier nun zehn Heilige in großer Dichte. Darunter herausragend vier von ihnen. Links Petrus in ungewöhnlichem Blau-Gelb. Sein Gegenspieler der schön gewachsene Sebastian sowie auf der ersten Stufe sitzend Katharina von Alexandria in nuancenreicher Komplementärfarbigkeit. Desgleichen herausgehoben der kniende Abt Bernhard von Clairvaux, zu dem sich Maria hinwendet. Das Ganze: ein zu wenig beachtetes Meisterwerk!

Instead of Raphael’s unfinished Madonna del Baldacchino, Ranieri Dei commissions Rosso Fiorentino. His altarpiece for the family chapel in Santo Spirito was replaced by a copy at the end of the 17th century. The original was moved to the Palazzo Pitti. I have deleted the 18th century all-round enlargement here.

Mary with Child in a similar conception to the figures in the Pala dello Spedalingo. But the whole is also an echo of Raphael’s composition, which is only 14 years older. Instead of Raphael’s four, there are now ten saints in great density. Four of them stand out. Peter on the left in magnificent blue and yellow. His counterpart the beautifully grown Sebastian and, seated on the first step, Catherine of Alexandria in nuanced complementary colors. The kneeling Abbot Bernard of Clairvaux, to whom Mary is turning, is also highlighted. The whole: an under-appreciated masterpiece!

Florenz, Rosso Fiorentino: Moses wütet in Midian –Auseinandersetzung mit Michelangelo

Rosso Fiorentino, Moses verteidigt die Töchter des Jethro, 1523, Öl auf Leinwand, 160 x 117 cm, Florenz, Uffizien

Das 1523 in Rom gemalte dramatische Szene entstammt dem Alten Testament. Hirten verhindern, dass die sieben Töchter des Priesters Jethro am Brunnen Wasser für ihre Tiere holen (2. Mose 1:16-21). Ein herkulischer Moses greift ein und schlägt die Hirten zu Boden. Rosso gestaltet einen unerbittlichen Kampf fast nackter Männer, wobei er viel den Aktdarstellungen Michelangelos verdankt.

Nach dem Sacco di Roma ist Rosso Fiorentino vielerorts in Italien tätig. 1530 aber bricht er nach Frankreich auf, um in den Dienst von König François I. zu treten, vor allem in Fontainebleau.

The dramatic scene painted in Rome in 1523 comes from the Old Testament. Shepherds prevent the seven daughters of the priest Jethro from fetching water for their animals at the well (Exodus 1:16-21). A Herculean Moses intervenes and knocks the shepherds to the ground. Rosso depicts a relentless battle between almost naked men, owing much to Michelangelo’s depictions of nudes.

After the Sacco di Roma, Rosso Fiorentino worked in many places in Italy. In 1530 he left for France to enter the service of King François I, particularly in Fontainebleau.

1523, vor gut 500 Jahren gemalt: erschreckte junge Frauen – gewalttätige Männer, Detail des vorigen. Die hier gezeigte älteste Tochter Zippora gibt Jethro Moses zur Frau.

1523: frightened young women – violent men, detail of the previous one. The eldest daughter Zipporah, shown here, gives Jethro Moses in marriage.

Florenz, Rosso Fiorentino: Kinderglück in Engelsgewand

Rosso Fiorentino, Madonna dello Spedalingo, Detail, Florenz, Uffizien

Nochmals das einmalige Engelspaar der Pala dello Spedalingo, das in seinem Liebreiz ein friedvolles Gegengewicht zu den Hauptfiguren ist.

Once again, the unique pair of angels from the Pala dello Spedalingo, whose charm provides a peaceful counterbalance to the main figures.

Rosso Fiorentino, Musizierender Engel, 1521/24, Öl auf Holz, 39 x 47 cm, Florenz, Uffizien

Von vergleichbarer Anmut wie das Engelmädchen des letzten Details ist ein weltbekanntes malerisches Juwel des Künstlers und der Uffizien. Kind und Instrument sind eins: hellwaches Lauschen, versunken in die von den Händchen hervorgebrachten Töne. Großartig der Farbakkord vom hellem Mohnrot (Coquelicot), den Federn und dem Gold der Laute. Farbtöne, die sich im wuscheligen Haar vermischen.

Of comparable grace to the angel girl in the last detail is a world-famous pictorial jewel by the artist and the Uffizi. Child and instrument are one: wide-awake listening, immersed in the sounds produced by the little hands. The color chord of the bright poppy red (coquelicot), the feathers and the gold of the lute – hues that blend in the tousled hair – is magnificent.

Rossos Bilder wirken wie Plastiken, dreidimensional, sehr beeindruckend, offenbar zu expressiv für einige seiner Auftraggeber. Großartig fotografiert!

Danke lieber Christian!

Willi