Florenz, Artemisia Gentileschi: Judith und Holofernes, um 1620, Öl auf Leinwand, 199 x 162,5 cm, Uffizien

Laut Altem Testament (Judit 12.13) sucht die mutige Jüdin schutzlos den assyrischen Heerführer Holofernes in seinem Feldlager auf. Begeistert von der Weisheit und Schönheit der jungen Witwe, beabsichtigt Holofernes sie bei einem Trinkgelage zu verführen. Total betrunken, kommt es nicht dazu. Judith enthauptet ihn mit seinem eigenen Schwert. Damit rettet sie die Stadt Betulia und ihr Volk. Vgl. Donatello und Michelangelo mit ihren Befreiungsidolen.

Artemisia Gentileschi (1793-1653), jung vergewaltigt von ihrem ersten Lehrer Agostino Tassi (1778-1644), übertrifft alles an Drastik, sogar Caravaggio. Judiths Magd hält mit aller Kraft die Arme von Holofernes, sodass er sich nicht wehren kann.

Florenz, Artemisia Gentileschi: Tyrannenmord

According to the Old Testament (Judith 12.13), the courageous Jewish woman seeks out the Assyrian army commander Holofernes in his camp without any protection. Intrigued by the young widow’s wisdom and beauty, Holofernes intends to seduce her during a drinking session in his tent. Drunk, it does not come to that. Judith beheads him with his own sword. In doing so, she saves the city of Bethulia and its people.

Artemisia Gentileschi (1793-1653), raped at a young age by her first teacher Agostino Tassi (1778-1644), surpasses everything in drasticness, even Caravaggio. Judith’s maid holds Holofernes‘ arms with all her might so that he cannot defend himself.

Judith verrichtet ihr Werk mit großer Anstrengung und Widerwillen. Das Schwert dient ihr nicht zum Schlagen, sondern – ähnlich wie bei Caravaggio – zum Abschneiden des Kopfes. Sterbend blickt Holofernes auf den Betrachter.

Judith carries out her work with great effort and reluctance. The sword is not used to strike her, but – as in Caravaggio’s work – to cut off her head. Dying, Holofernes looks at the viewer.

Ende der florentinischen Bilderfolgen

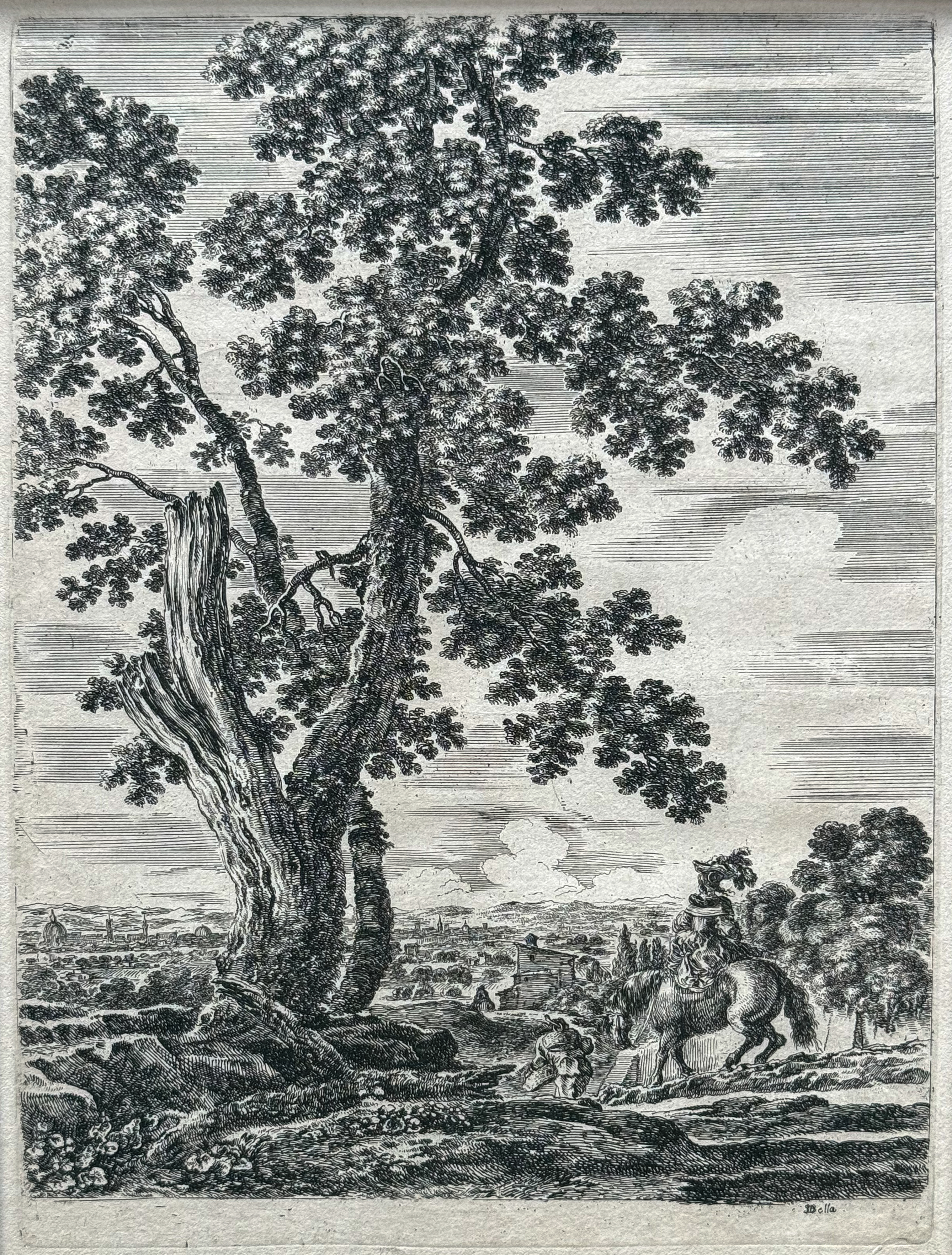

Stefano della Bella (1610-1664), Tal des Arno, Privatbesitz

Noch ist Florenz in der Ferne. Bauern mit Körben und eine Reiterin mit Federhut sind auf dem Weg zur Stadt. Auch mich lockt sie zu einem erneuten Besuch.

Florence is still in the distance. Farmers with baskets and a horsewoman in a feathered hat are on their way to the city. It also entices me to visit again.

Ausklang: die Hausruine von Gibellina, dem sizilianischen Örtchen, das 1968 einem Erdbeben zum Opfer fiel. Ich zeigte sie bereits als Leitmotiv in meinem ersten Beitrag zu diesen florentinischen Bilderfolgen.

Oben auf die Fassade hat jemand den Satz geschrieben, der für alle Zeit gilt:

„COSA SAREBBE L’UOMO SENZA IL SOFFFIO RIGENERATORE DELL‘ ARTE ?“– „Was wäre der Mensch ohne den wiederbelebenden Hauch der Kunst?“

Conclusion: the ruin of Gibellina, the Sicilian village that fell victim to an earthquake in 1968. I already showed it as a leitmotif in my first contribution to this Florentine picture series.

At the top of the façade, someone has written a sentence that applies for all time:

„COSA SAREBBE L’UOMO SENZA IL SOFFFIO RIGENERATORE DELL‘ ARTE ?“– “WHAT WOULD MAN BE WITHOUT THE REGENERATING BREATH OF ART?”